Performance criteria is one of the most—if not the most—important aspects of a successful preventive maintenance (PM) and condition-based maintenance (CBM) program. The asset owner must refine and accept all performance criteria for it to be meaningful, and the criteria must be documented to ensure consistent application. Specifically, when referencing national and international consensus standards as a basis for a facility's performance criteria, personnel must evaluate the criteria to ensure it is representative of the normal operating characteristics of the asset. In all of the CBM (and predictive maintenance [PdM]) courses I have developed over the years, I have always shared the following: "It is the facility owner's responsibility to establish performance standards (objective criteria). Any defined performance standards should provide alarm values and shutdown values." If consensus standards or even original equipment manufacturer (OEM) recommendations are used as a basis for specific asset performance standards, those recommendations must be evaluated and, in most cases, adjusted to fit a specific set of asset operating conditions. The facility owner's engineer is typically responsible for that decision. Documenting the criteria and providing training are also necessary to ensure that the defined performance criteria are globally understood and that consistent and coherent data is collected for analysis. Ask yourself: Has your facility made this level of investment in its PM and CBM programs?

Low-Frequency Vibration Monitoring

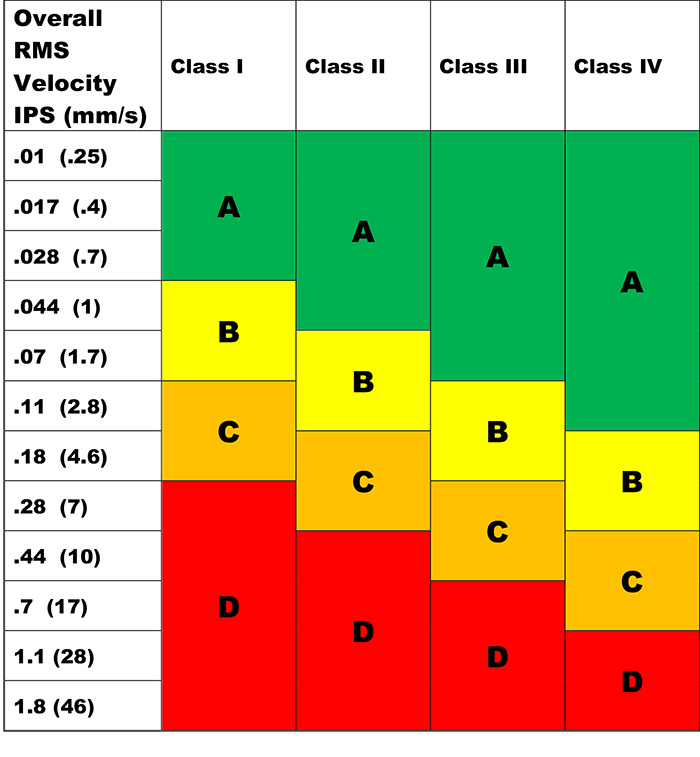

The following discussion focuses on broadband, filter-out, low-frequency vibration monitoring (less than 2 kilohertz [KHz]). The discussion also deals with International Organization for Standardization (ISO) consensus standards associated with general equipment vibration. The notions and concepts presented in this article are also applicable to those consensus standards that directly apply to in-situ pumps and fans, Hydraulic Institute and Air Movement and Control Association (AMCA) International. In the days before ISO 10816, Mechanical Vibration – Evaluation of machine vibration by measurements on non-rotating parts, Parts 1 through 6, there was ISO 2372, Mechanical vibration of machines with operating speeds 10 to 200 rev/s – Basis for specifying evaluation standards. ISO 2372 was replaced by ISO 10816 in 1995. One example of performance criteria that must be evaluated and adjusted to fit a specific set of asset operating conditions is the old\'97from 1974—ISO 2372 Vibration Severity Chart. A version of this chart is packaged with just about every vibration meter, vibration analyzer and vibration data collector on the market today. It is still referenced 20 years after ISO 2372 was withdrawn. After 40 years of presentation, you would think that most would understand that this chart is not an absolute—it provides guidance only. It offers a place to start when developing a CBM process. This chart was also referenced in the original ISO 10816 (ISO 10816-3, to be specific) as an appendix. In more recent revisions of ISO 10816, the appendix has been removed and the severity chart has been rewritten. However, no matter what color you paint it, the severity chart is still there. ISO 10816 (the original and the latest iteration) also contains the following statement: "The ISO does not provide pass or fail criteria. It provides reasonable guidance ensuring that gross deficiencies (read as unsafe) or unrealistic requirements (read as too limiting) are avoided." For whatever reason, few people notice this statement. Many technicians and engineers see the charts and tables and jump to the conclusion that these are absolutes. Figure 1 (page 72) shows a variation of the old 2372 severity chart. Several things are important to note:- The severity chart is no longer specifically referenced in a consensus standard.

- The chart is not used as pass or fail criteria but as general guidance.

- It is the facility owner's responsibility—not a third-party committee's—to establish performance standards (objective criteria).

Case Study

As an example, a global manufacturer with a fleet of facilities in the U.S., Taiwan, China, Japan and Korea that has been in business for more than 100 years drank the ISO 2372 Kool-Aid. During initial visits to each facility when the technicians walked through their vibration monitoring program(s) for small-frame pumps, they showed their latest manual data collection and on-line monitoring schemes. Figure 1. A variation of the ISO 2372 severity chart (Courtesy of ARES Corporation)

Figure 1. A variation of the ISO 2372 severity chart (Courtesy of ARES Corporation)- "The vendor that sold us the monitoring equipment set the alarm values."

- "The commercial vibration training course I attended referenced these alarm values."

- "These are ISO alarm values."