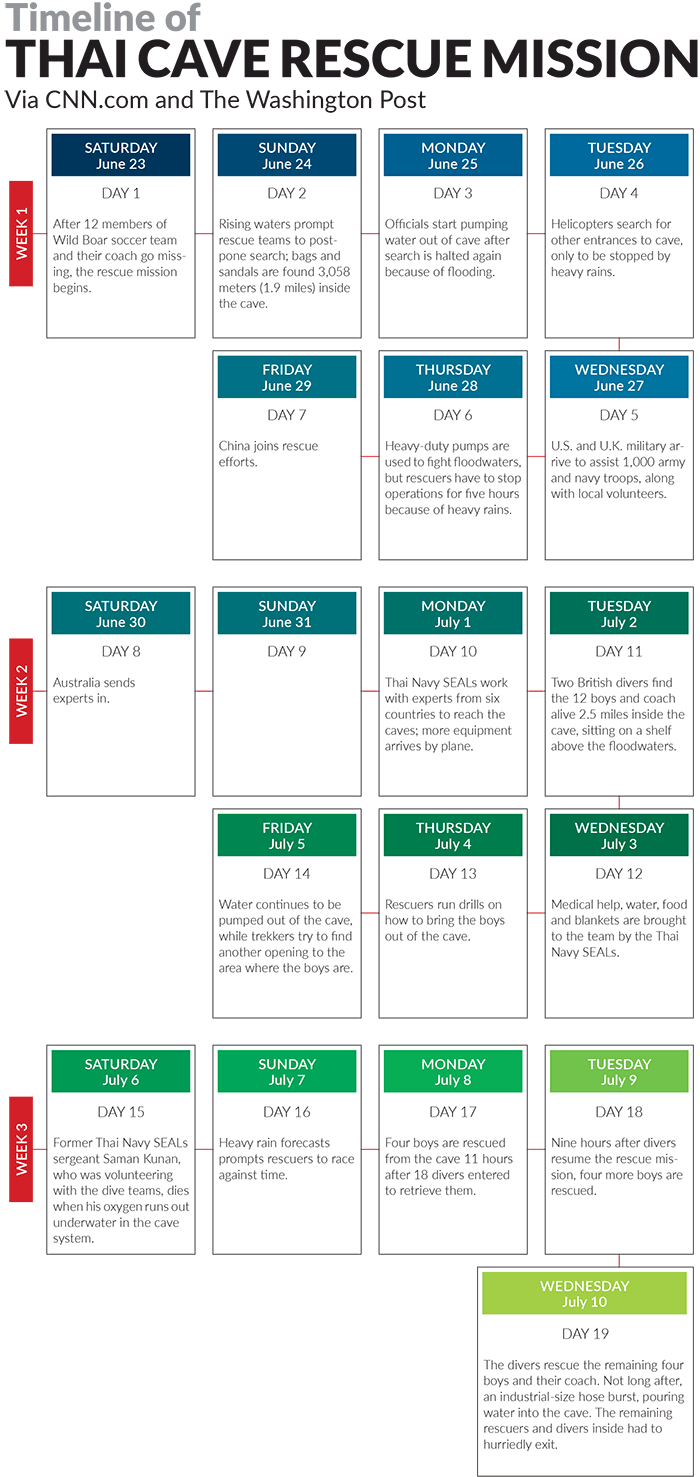

The pump industry was quickly called into action in late June when 12 members of a junior soccer team along with an assistant coach were trapped in a cave in Thailand’s Chaing Rai Province.

Heavy rains, rising water levels and strong currents endangered the group and kept them stranded.

More than 10,000 people aided in the rescue, including divers, rescue workers, governmental agencies and pump engineers. Companies including Xylem, Sulzer and Kirloskar Brothers all played a part in aiding the rescue, which culminated on July 10 after the team was trapped for 18 days in a chamber more than 2.5 miles from where they entered the cave.

Image courtesy of Adobe Stock

Image courtesy of Adobe StockXylem had engineers on-site to aid in the rescue. Company CEO Patrick Decker was in Thailand with his wife before Singapore Water Week from July 8-12. He saw nonstop coverage of the event on Thai TV and tried to get in touch with officials in charge of the rescue, he said. He secured a phone call with the governor of Chaing Rai.

According to The Washington Post, a truck with a small industrial pump was on-site early in the rescue efforts, but more were needed. Within three days of the start of the June 23 crisis, more than 40 pumps had arrived. According to The Post, pumping power stabilized the water level and lowered it on drier days while removing more than 400,000 gallons per hour. This flooded fields of 128 farmers, who lost their rice harvests for the year.

Sulzer confirmed that they had pumps on-site, but declined to go into specifics. Company representatives have not spoken publicly about the rescue.

According to its press release, Kirloskar Brothers had team members on-site since July 5 and offered to allocate four specialized high-capacity Autoprime dewatering pumps. These were kept ready at the Kirloskarvadi plant to be airlifted to Thailand for the rescue operation.

Tassanai Poopat, who works in Xylem’s Thailand office, went to the cave during the discovery process and noticed around 20 pumps on location, but only five were operational due to insufficient electricity and tight spaces, Decker said. Poopat along with Ryan Ng from Xylem's Singapore office, Bob Spinner from the dewatering headquarters in Bridgeport, N.J., Adam Drakeley from the Xylem primary dewatering pump manufacturing facility in Quenington, England and Chong Hin Koh, managing director for Southeast Asia from Singapore, were all on site at various points.

The pumps were large and had to be hand carried by Navy SEALs to their locations in the cave, Decker said. But the pumps that were immediately available were not suited for the setting.

The rescue area was overwhelmed with people and no more pumps were needed, Decker was told, but he said the governor was impressed that Xylem had a worker there to survey. Decker was able to get two of the company’s top dewatering applications engineers to the site by Saturday, July 7. There were five representatives from Xylem at the site at various times during the event.

Xylem came up with two plans. The primary one assumed they would not be able to get pumps they believed were fit for the purpose and would work with what was on-site. The backup plan, which was not needed since the boys were rescued, was focused on deciding what pumps would fit, what they would look like and how the company could get them there.

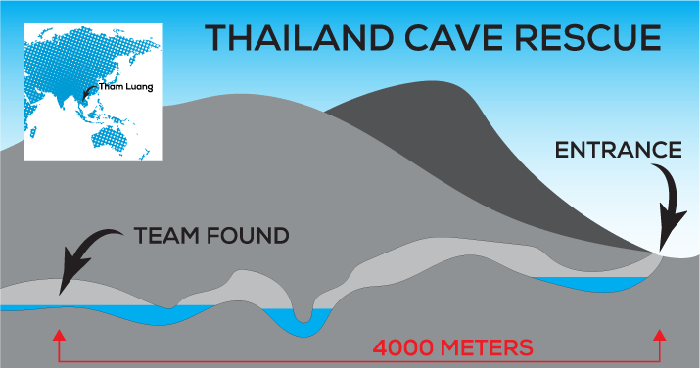

There were four chambers rescuers had to go through to get the team out. Decker said that on Friday before his team was able to get in, Chamber 1 was muddy but clear. Chamber 2, a few hundred meters in, had water that was knee-high. Chamber 3 was U-shaped, in a tight space and full of water. Chamber 4 was a kilometer in length and also full of water.

The Thai rescue team and the Xylem workers were able to help increase flow rate by 40 percent.

“Imagine a handful of pumps sitting at entrance of the cave and they’ve got hoses that are going up to a kilometer into the cave,” Decker said. “You’ve got limited power supply and you’re going to have a lot of offtake of the water in terms of leaks but also depressurization and by the time you get to the end of that hose, very little power supply is there.

“They helped the team slice the hoses and basically set up a relay. Rather than having five pumps all operate on their own, they basically reduced that and said, ‘How do we set up a relay of the pumps of the 20 to where they are not requiring that much electricity, but using the pumps to push the water along and each one helps along the way.’ They ended up recabling the electrical supply and that was a big increase in the flow rate as well.”

Click here to download a printable version of this timeline.

Click here to download a printable version of this timeline.The assistance from the Xylem team helped rescuers deal with the realities of the situation.

“There were a few things they did to change it. It was pretty basic. It wasn’t the obvious solution per se, but it was getting access to the decision-makers and to understand that what they thought was a really good flow rate with a lot of water coming out, when our team got in there, they could show them that you could almost double what you’re doing here.”

These efforts set up the rescue. When the extraction process started, only Navy SEAL rescue workers were allowed within 3 kilometers of the cave.

On Sunday (July 8), when the rescue began, Decker said Chamber 3 was muddy and passable and the water level of Chamber 4 was lowered down to the shoulder level of an adult – high for children, but providing enough space that the governor felt comfortable going ahead with the extraction exercise. Decker said the governor was worried about the lower oxygen levels where the team was situated.

“At the end of the day, all the credit goes to the local Thai team,” Decker said. “They were the ones who actually did it. They saw a window, took advantage of it and worked out a plan.”

This video footage from our @XylemInc colleagues helping on the ground in Thailand shows how challenging the cave conditions were. Their expertise helped #TeamThailand optimize the #pumps onsite, to assist in #ThaiCaveRescue. So proud of their contribution! pic.twitter.com/2haU4KcXTf

— Kelly McAndrew (@mcandkm) July 13, 2018

Many reports came out indicating that, after the boys and coach were rescued, the main pump failed. But, according to The Washington Post, one of the industrial-size hoses burst, sending water back into the cave. Rescuers and divers still inside had to hurry, but made it out alive. A former Thai Navy SEAL died during the rescue efforts on July 6 while attempting to deliver oxygen to the trapped teens and their coach.

Decker felt that news reports of the “pump fail” shed a bad light on the local rescue operation.

“The back story is they had another dozen or so pumps that they could deploy immediately that were in the cave,” Decker said. “They weren’t the pumps that were for purpose in that cave. They happened to be there.

“I don’t like it because it almost makes it feel a little bit like the people on the ground were running that operation were a little bit irresponsible. I know, from our guys on the ground, it was anything but that. It was very disciplined. The local team was on it and they had the backup if they needed it.”

If the initial rescue operation had to be delayed or diverted, Xylem had flown in some smaller, submersible handheld pumps that were more powerful, lightweight and could be carried farther. If needed, Chamber 4 could have been drained, Decker said.

Xylem, which also helped in the 2010 Chilean mine rescue, left the pumps behind for training purposes if they have to use them again.

This is another example of the pump industry being there in a time of need.

“At end of the day, this was a Thai-led operation,” Decker said. “The governor of Chaing Rai had to call all the shots. He was under an incredible amount of stress. All your job is when you’re in these situations is to give whoever the leader is of the operation some options and a way out. Our role was to lower the water level and if that did not work, bring in the backup plans with pumps to give them another option if the boys could not make it through Chamber 4.”