Maintenance personnel in industrial plants and facilities know a great deal about pumps. They can replace seals and bearings in a jiffy, remove and install pumps and generally fix anything that goes wrong mechanically. They know how, because many of them do it a lot—on the same pumps, month after month. Plant engineers know how to read a data sheet and (often with the help of a pump manufacturer) can spec pumps to meet flow, pressure and service requirements. Pumps can be properly sized initially for ideal conditions when a system is designed. The only problem is those conditions in the process are dynamic and rarely stay the same over the life of the pump, so it may not be the ideal pump size for the conditions five years from now. But it can be difficult for these maintenance technicians and plant engineers to tell when a pump is having problems, performing badly or is about to fail. So many pumps run to failure. A big part of the problem is the lack of sensors on many pumps, resulting in insufficient data to detect common problems, such as:

- vibration that can damage pumps, pipes and foundations

- cavitation that can destroy impellers and volutes

- “dead head” operation (zero flow) that can overheat the liquid, maybe causing the liquid to flash to vapor

- seal pot leaks of toxic, hazardous

- or corrosive fluids

- excessive pump case pressure or pressure spikes that can damage pump seals

- excessive temperature within a motor that can cause damage

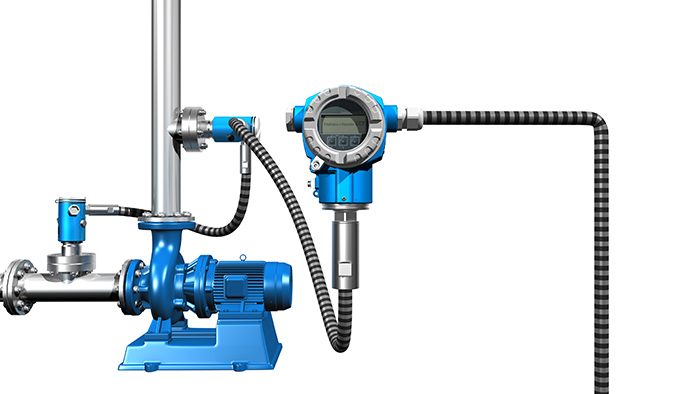

Image 1. An electronic differential pressure (EdP) transmitter is well suited for monitoring the performance of a pump. An EdP transmitter can monitor the suction and discharge pressure of a pump and its temperature. (Courtesy of Endress+Hauser)

Image 1. An electronic differential pressure (EdP) transmitter is well suited for monitoring the performance of a pump. An EdP transmitter can monitor the suction and discharge pressure of a pump and its temperature. (Courtesy of Endress+Hauser)Adding Instrumentation

Most pumps already have (or should have) a flow meter to monitor pump discharge flow rates. Pumps also need a differential pressure (DP) instrument and a temperature instrument. A DP instrument can monitor the suction and discharge pressure—i.e., the differential pressure—of a pump. Too high or too low suction and discharge pressures can cause or indicate various pump issues such as cavitation, loss of flow, mechanical failure, vibration issues, excessive noise, or bearing and sealing wear. And some newer electronic DP devices have built-in temperature measurement capabilities (see Image 1). Temperature instruments can measure pump, fluid and motor temperatures. To avoid cavitation, the net positive suction head (NPSH) available must be greater than or equal to the NPSH required with a safety margin. Monitoring the suction head identifies conditions that can damage the pump.Several factors can change the NPSH required, including increases in flow rate and changes to the pressure or liquid level in a supply tank in front of the pump. “Smart” flow meters are available that can diagnose problems such as entrained air, vibration (which could be caused by pump cavitation), coating, corrosion and inhomogeneous or unsuitable media (see Image 2)..jpg) Image 2: One type of Coriolis flowmeter not only measures flow, it detects problems.

Image 2: One type of Coriolis flowmeter not only measures flow, it detects problems.Training the Pump Experts

Even if pumps are instrumented properly and the data from these instruments is analyzed with a pump monitoring system, the engineers and maintenance personnel may not know what to do with the data without proper training. In some cases, the instruments indicate a problem, but expertise is needed to determine the best fix..jpg) Image 3. An instrumented pump training unit demonstrates principles taught in the classroom

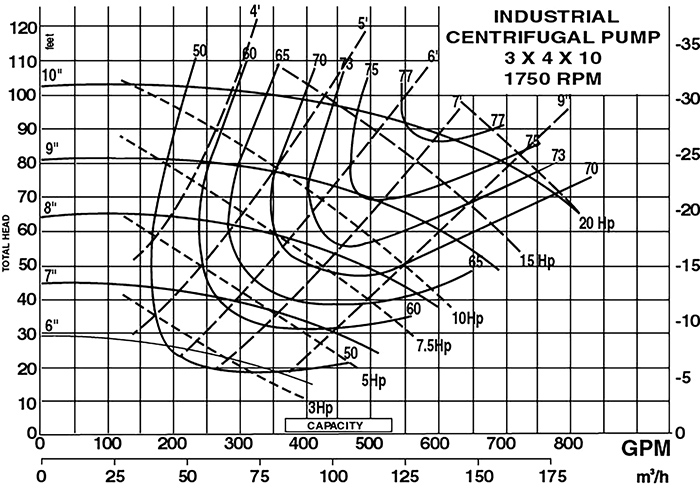

Image 3. An instrumented pump training unit demonstrates principles taught in the classroom Figure 1. Typical pump curve. Training helps engineers and maintenance people understand it.

Figure 1. Typical pump curve. Training helps engineers and maintenance people understand it.