For Guy and Katherine Shropshire, whose family has been growing salad vegetables on their land in the United Kingdom for more than 60 years, the health benefits and family tradition associated with beets were worth sharing. So in October 2010, the husband-and-wife duo ventured across the Atlantic to a food festival where they introduced their specialty marinated beet recipes to America. The event was wildly successful, leading the Shropshires to start a beet business in the U.S. They called it Love Beets. The company began selling packaged products shipped from its U.K. parent company G’s. But when business began to boom, the 60,000-square-foot U.K. facility could no longer keep up. “There’s a finite capacity of the number of tons that can be put through that facility,” said Simon Woods, Love Beets quality assurance manager. “We were at that capacity. We had to do something.”

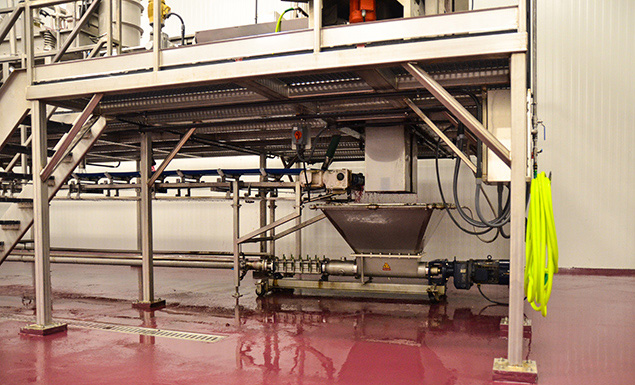

Image 1. The pumps are low to the ground and can be rolled under production equipment to capture waste and pump it out of the facility. (Images courtesy of SEEPEX Inc.)

Image 1. The pumps are low to the ground and can be rolled under production equipment to capture waste and pump it out of the facility. (Images courtesy of SEEPEX Inc.)The Challenge

“With America being about seven times larger than England, population-wise, the math was right to build here and serve 300 million Americans on their doorstep,” Woods said. To ensure the process maintains a hygienic and sanitary environment required for food production, the Rochester facility includes separate rooms, segregated air-flows, stainless steel walls, a nonslip floor and high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration. The temperature is set to 38 F at all times, and the production team maintains food-grade safety protocol. Woods says the facility is “nearly as clean as surgery rooms.”.jpg) Image 2. The facility processes between 130 and 140 tons of beets every week.

Image 2. The facility processes between 130 and 140 tons of beets every week.