When it comes to pump operation and maintenance, a strategy using asset performance management (APM) can provide substantial benefits from the perspectives of system uptime, asset longevity and both capital and operating expenses. To build an APM strategy to guide pump operation and management, organizations should examine these three areas, in this order: business model, system criticality and appropriate monitoring.

Business Model: Is the Organization Primarily Profit Driven or Risk Driven?

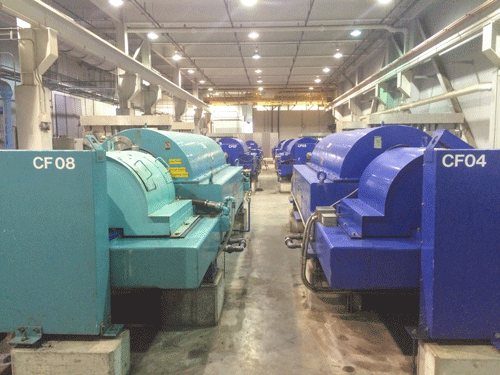

Municipal operators, such as water utilities, are generally more risk driven. Their prime mission is public health through the reliable delivery of clean water and the removal of wastewater. Water quality and level of service delivery are the highest priority. As a result, water utilities typically put more resources toward redundancy and other protocols that help them avoid outages and reduce risk.

Industrial operators, on the other hand, are more profit driven. Their main concern is maximizing output while minimizing costs, with greater focus on efficiency and output and less focus on redundancy. Downtime is a problem only if it affects profitability.

An organization’s business model influences how it operates its assets. Municipal operators typically take an “unequal runtime” approach, which involves having spare pumps at the ready in case of an unexpected shutdown. Industrial operators typically take an “equal runtime” approach in which all the assets are in lead mode (or all off for scheduled refurbishment and maintenance).

The business model that governs the operation will influence both the opportunities for cost savings and the degree of attention and monitoring the pumps require.

System Criticality: How Critical Are the Systems & Assets in the Plant?

Not all systems in a plant are equally important to the overall process, and not all assets in a system are equally important to that system. The business model will influence the criticality of various pumping systems and pump assets in the overall operation. Organizations need to analyze their systems and assets to determine which are the most critical to their mission and are therefore in need of the largest monitoring investment.

“Very high critical” assets are those that absolutely cannot go down without advanced notice. Because these systems are so important, they require continuous monitoring through supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) or internet of things (IoT) devices so that an unexpected shutdown does not occur. Beyond this top-level of criticality, assets can be categorized as “high critical,” which require continuous but not continual monitoring, or “medium critical,” which require only periodic monitoring.

Data collected from every level of monitoring should have value commensurate with its criticality. It should be relevant and frequent enough to catch impending failures with enough time for plant operators to take corrective action, but not so frequent that it results in wasted time, money or resources.

Generally speaking, the equal runtime industrial business model will categorize a higher percentage of assets as very high critical and in need of continuous monitoring, because unlike municipal operations, they do not invest in as much redundancy. A treatment plant will usually have backup pumps in case of an unexpected asset failure or shutdown.

Appropriate Monitoring: Is the User Monitoring the Right Assets With the Right Tools to Get the Right Data?

Monitoring data should be directly linked to how an asset fails and be able to tell operators which component is failing and why. Assets typically fall into two broad groups:

The first group is dynamic, rotating assets, such as pumps, gears and motors. Impending failure of this type of asset is typically indicated by vibration, temperature, oil degradation and other symptoms related to uncontrolled energy, often characterized by exponential decay curves. Examples of monitoring tools for dynamic assets are shock pulse, oil analysis and even hand touch (but only if it can be done safely).

The second group is non-dynamic, non-rotating, stationary assets, such as pipes, mountings and structures. Impending failure indicators for this type are often rust, corrosion, pitting and bending and are often characterized by linear decay curves. Examples of monitoring tools for non-dynamic assets are ultrasound, stray current and x-ray.

Next, the speed of failure is an important factor in choosing monitoring tools because certain assets will fail quickly and others will fail slowly. For example, bearings and other dynamic assets can fail in days to weeks, while coatings can take years to cause failure in non-dynamic assets. Knowing how quickly certain assets fail for specific reasons will help dictate how sensitive and sophisticated the equipment should be to catch the failures before they get too far. Selecting the right sensor is also informed by how important or critical this asset is and if it is worth investing in more resource-intensive monitoring.

Lastly, direct information, such as vibration and temperature, is a much more precise and valuable indicator of the problem than indirect information, such as reduced efficiency or output.

Reduced efficiency or output could be the result of a bad motor or coupling, a bearing getting tight, the separation between the impeller and volute beginning to get too big or any number of other reasons. Indirect information suggests further investigation is required but is often not specific enough to point to appropriate remedial action.

Using Asset Performance Management to Get the Most Value

Monitor the right things. To use a rough analogy, if someone is planning to drive across the country in their car, they would be smart to keep an eye on tire pressure, oil level and the amount of gas in the tank, but checking the state of the car’s paint would not be useful for assessing the car’s ability to make it and would be a colossal waste of time. If interested in keeping pumps running smoothly and consistently, users need to keep an eye on the parts that wear quickly and do so with the right sensors.

Everything costs money, so run the numbers. Operators must weigh all of the cost of monitoring to prevent outages against the cost of the downtime and repairs caused by the outage. It is best to reserve the expensive, highly sophisticated continuous monitoring for the very high critical assets, regardless of the business model.

APM strategies help asset owners optimize their operations and maximize asset value. Facilitated by appropriate asset monitoring tools, risk-based decisions will then be able to support their business model and mission. By using an APM framework, pump operators can extend the life of their assets, save money and avoid system failure. A system in which critical assets almost never go down unexpectedly delivers greater production/profitability assurance for industrial operators and greater level of service assurance for municipal operators.