Denver’s Coors Field replaced old chopper pumps in its underground vault to better manage runoff, potential flooding and the 200,000 gallons used for cleaning.

BJM Corp.

11/01/2016

Denver’s Coors Field—home to the Colorado Rockies Major League Baseball (MLB) franchise—began operations in March 1995 after two-and-a-half years of construction. Built in the “retro-classic” architectural style popular at the time, the stadium sports red brick and green painted exposed steel that embody the spirit of America’s favorite pastime.

Image 1. Coors Field features an innovative drainage system. The infrastructure is designed to handle a 100-year flood because

of the field’s proximity to the South Platte River. (Images courtesy of BJM Corp.)

Image 1. Coors Field features an innovative drainage system. The infrastructure is designed to handle a 100-year flood because

of the field’s proximity to the South Platte River. (Images courtesy of BJM Corp.)The Challenge

During baseball season, the water—and any trash and debris collected with it—is pumped out of the vault and into the storm sewer system. In the off season, a much smaller amount of collected water is pumped out and diverted to one of several small detention ponds to evaporate. The pumps that do the heavy lifting of moving the collected water out of the vault were replaced in May 2015. The original pumps were chopper pumps installed in 1998 and were showing signs of wear—moisture was getting into the motors. Since 1998, pump technology has come a long way. One goal of the replacement was to incorporate more modern technology into the system. Coors Field personnel wanted a pump that had good shredding capability and was made of durable materials. When it became evident that the old pumps needed to be replaced—they were 17 years old and showing signs of wear—Young and James Leflar, an engineer and member of the Coors Field HVAC team, contacted Phoenix Sullivan, their representative at Denver Industrial Pumps.The Solution

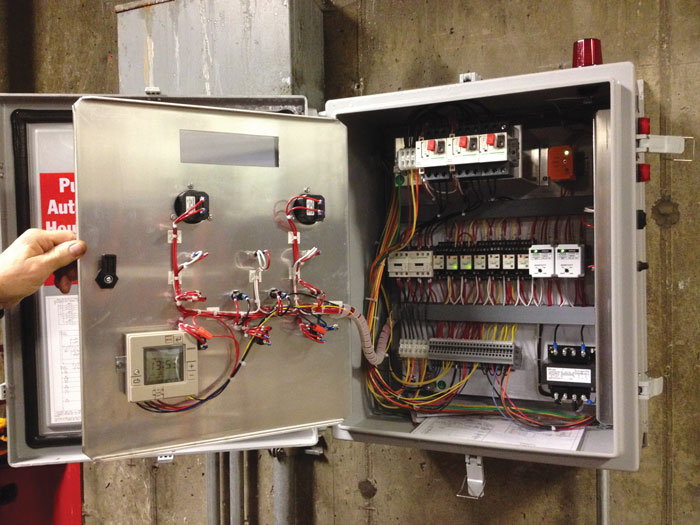

Sullivan recommended that the old chopper pumps be replaced with two submersible shredder pumps. “The customer needed a pump that could handle debris getting into the vault/sump and not clogging the pump,” Sullivan said. “The (shedder pump we chose) has a cutting tool that cuts and shreds the debris ... allowing it to pass without clogging the pump.” Image 2. The contracted pump company was able to fabricate a custom VFD control panel at the ballpark’s request.

Image 2. The contracted pump company was able to fabricate a custom VFD control panel at the ballpark’s request.  Image 3. The drainage system collects the runoff in a huge vault under the parking lot at the rear of the stadium. Debris such as peanut shells, straws and cups end up in the vault, which can hold up to 1 million gallons.

Image 3. The drainage system collects the runoff in a huge vault under the parking lot at the rear of the stadium. Debris such as peanut shells, straws and cups end up in the vault, which can hold up to 1 million gallons.