Gaskets are crushed more frequently than many end users realize. Some maintenance professionals claim that is all they see when they separate a leaking flange. Many simply replace the gasket rather than investigating the cause of the failure in depth. Gasket crush is a significant threat to plant reliability. This problem causes leaks, which can lead to a dangerous plant situation, especially if a hazardous fluid is involved. This issue is unpredictable and introduces variability into plant operations. All types of gaskets—metal, nonmetal and composite—experience gasket crush. If a gasket design fails on the first installation, plant personnel can replace it with a new design during the next plant shutdown. However, if a gasket has worked nine times without a problem, then leaks on the tenth installation because of gasket crush, an unplanned maintenance response is required. Users have two options for reducing gasket crush: better torquing procedures, which can be difficult, and better gasket design, which is easier to implement.

Torquing Procedures

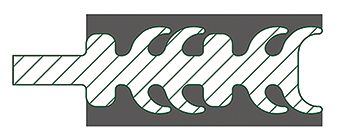

In a crushed gasket, different compression patterns are visible—sometimes on one side of the gasket, sometimes on opposite sides and sometimes all over the gasket. These patterns point to over-compression. The most obvious conclusion is that something was wrong with the torque, even though sophisticated torque equipment, such as torque wrenches or bolt tensioners, is often used during installation. Figure 1. Round-edged beveled ribs compress under pressure. (Graphics courtesy of AIGI Environmental Inc.)

Figure 1. Round-edged beveled ribs compress under pressure. (Graphics courtesy of AIGI Environmental Inc.)- Bolts must be well-lubricated with a lubricant of known coefficient of friction, because unlubricated bolts can consume up to 50 percent of the torque load.

- Torque typically is calculated based on the bolt material, not the required load of the gasket material, which is usually too high for the gasket need.

- Personnel only have access to a recommended bolt load for the cool flange when the operation has not yet started. The crucial hot torque load value is rarely available.

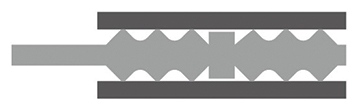

Figure 2. A stop-step feature prevents the flexible ribs from over-compressing.

Figure 2. A stop-step feature prevents the flexible ribs from over-compressing.Gasket Design

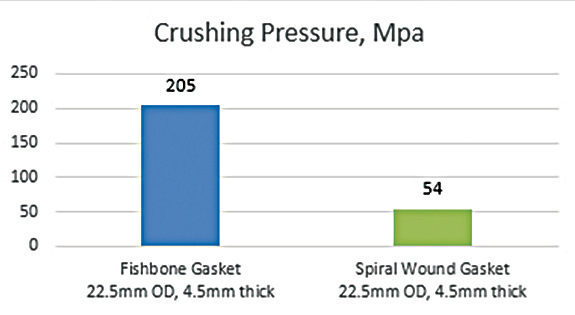

Designing better gaskets is a much easier solution in practice than attempting to deal with torquing procedures and the art of hot torquing. Spiral-wound and camprofile gaskets are the most commonly used metal gasket types. The compressibility and elasticity of spiral-wound gaskets are useful sealing characteristics. When paired with the strength that a camprofile gasket achieves through its unitary metallic structure, gaskets start to approach optimal design. Figure 3. Crush resistance test results, with a pressure of 205 MPa (29,732 psi)

Figure 3. Crush resistance test results, with a pressure of 205 MPa (29,732 psi) Figure 4. Spiral-wound gaskets have a tendency to unwind.

Figure 4. Spiral-wound gaskets have a tendency to unwind. Figure 5. Sharp edges in a camprofile gasket can lead to damage.

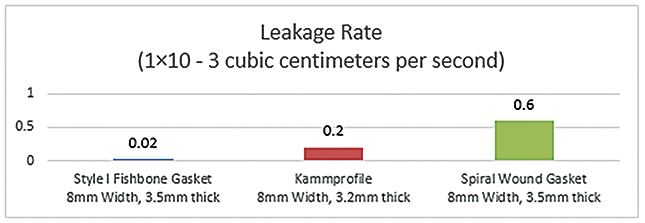

Figure 5. Sharp edges in a camprofile gasket can lead to damage. Figure 6. A leakage test compared the three gasket types. The gasket stress was 30 MPa (4,351 psi), and the nitrogen pressure was 4 MPa (560 psi).

Figure 6. A leakage test compared the three gasket types. The gasket stress was 30 MPa (4,351 psi), and the nitrogen pressure was 4 MPa (560 psi).