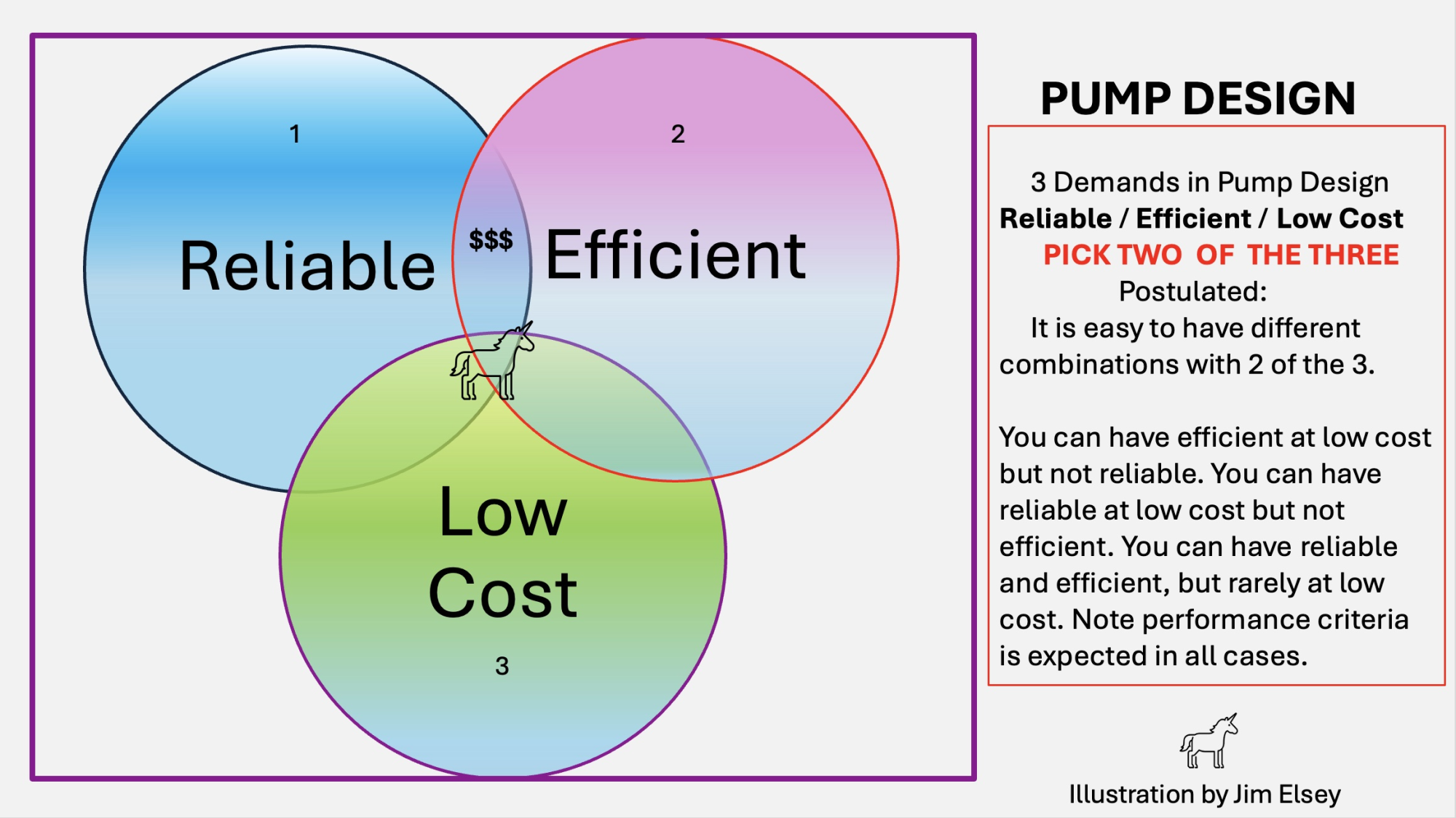

As a follow-up to my previous column on impeller design, let’s look at overall pump design from a 101 perspective. General pump design will invariably distill into a compromise between the three epiphanies of low cost, reliability and efficiency. You can readily have two of the three attributes, but to have all three is like finding a herd of unicorns.

Examples

The sump pump in my basement is low priced and reliable but is not efficient (I don’t care; I want the reliability). Similarly, the pump for my aquarium is low cost and reliable, but it too is not very efficient. The fish don’t complain. The pumps at my local wastewater plant are relatively expensive and very reliable but not very efficient. The water pump on my car is both reliable and subjectively efficient. However, I’m not convinced the water pump is inexpensive should you need to have one replaced. The boiler feed pumps (BFP) at my local power plant are very efficient and reliable but also extremely expensive. Note that most power plant BFPs are designed for a life of 30 years or more, and it is not uncommon for them to operate for 50 years, especially at base load plants with good maintenance teams.

See if you can think of similar examples in your experience and hypothesize if my premise rings true for your experience.

Economics

Because our market economy applies relentless pressure to commoditize almost everything, buyers will demand the least expensive pump. Often, in the transaction process, the reliability and efficiency of a pump will make a guest appearance in the specifications, but all too often these two attributes will be dismissed from the bid tabulation at a secret meeting at the eleventh hour. Not to be too negative here—I have seen improvement in efficiency considerations in recent years, as the cost of power is also increasing.

To the people who will be trapped with operating and maintaining inexpensive pumps for the next 20-plus years, I recommend that you become involved in the whole specification and purchasing process. Get the efficiency and reliability you need up front.

Pump OEM Secret

Maybe it’s a paradigm shift for you, but start thinking of the buying and selling transaction as simply the cost/price of metal per pound. Not excluding our nonmetallic friends on purpose, we can also express price as the cost of some material per pound—or is it really value per pound? In contrast, you should appreciate that making the pump more reliable and efficient often requires more metal and/or more metal in sophisticated and complicated forms.

If you have the time and inclination, look at the hydraulics (pick a head, flow rate and efficiency) for a pump from 50 years ago and make note of the weight, then compare the data to a modern pump at the same speed with similar hydraulics. Like your favorite candy bar, I am sure the current pump will weigh less.

By the way, I believe one gauge of potential reliability in a pump is its mass (think weight). All other measures being equal, the heavier pump is likely to last longer. Without going down a rabbit hole on the subject, it has a lot to do with the ability to resist and/or mitigate forces and moments—stress and strain. All the generated vibrations, torque, thermal movements and dynamics have to go somewhere. Just one more reason why, when reliability is paramount, I prefer slower and heavier pumps. There are many exceptions, but those pumps are usually not cheap.

Pieces & Components

For the purposes of the column (with a few exceptions), let’s assume we are discussing the ubiquitous overhung, horizontal, single stage, end suction pump, as standardized in the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) B73.1 or International Standards Organization (ISO) 5199 descriptions. I will also include some selections from the American Petroleum Institute (API) 610 world.

A pump is comprised of pieces and components that include the impeller, shaft, casing, bearings, housing and stuffing box (mechanical seal chamber) with accompanied mechanical seal or packing and respective gland. I addressed issues with shaft diameter, shaft stiffness ratios and critical speeds in previous columns. Also addressed was the fact that as the shaft diameter increases, the bearings get bigger and more expensive, but more importantly, the area of the impeller suction eye gets smaller for shaft through the eye designs (not on overhung pumps). In any design, you will always fight the battles between suction-specific speed (Nss), net positive suction head (NPSH), efficiency and recirculation.

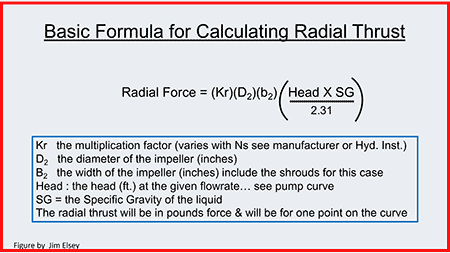

Radial Thrust

As the pump is operated away from the best efficiency point (BEP) in either direction, there is a significant increase in the radial thrust that must be addressed for the pump to remain reliable. One method to address radial force is to just treat the symptom and use bigger and/or higher load carrying bearings. Of course, the larger bearings are more expensive, but the other issue is now the shaft must also be bigger. Consequently, the bearing size is bigger overall (both inside and outside diameters), and so the bearing housing also needs to be bigger. Finally, if the shaft is bigger, so is the mechanical seal. Mechanical seals for a given model and material are priced by size.

At some point, the magnitude of radial thrust will approach a threshold where simply adding bigger bearings will not be feasible, and it becomes necessary for the manufacturer to address the actual radial thrust issue in lieu of the symptom. The manufacturer will then change or improve the volute from single to double as the casing diameter approaches the range of 10 to 14 inches. The dual volute design reduces the thrust almost in half (or at least to a more tolerable level), but the laws of physics will make you pay a reliability tax because dual volute casings are expensive to produce. There are also triple and quad volute designs at increased cost.

An alternative method to make the pump more reliable is to reduce the radial thrust by designing the pump with a concentric volute (the centerlines of both the volute and impeller will be the same). Of course, the pump will now be markedly less efficient. Note that offset designs, where the centerline of the impeller and volute are not congruent, allow the pump to be more efficient but with exponentially higher radial thrust components when operated away from the BEP and the preferred operating region.

For a fixed speed, as the impeller diameter and width increase, so do radial thrust, tip speed and impeller shroud torque. Due to material strength limits, there are corresponding head per stage limitations. Consequently, that single stage pump you were designing for a high head application will morph into an expensive multistage pump.

An alternative approach is to change to a diffuser design that reduces the radial thrust significantly but at a high cost. A diffuser is a complicated casting requiring extensive and precise machining. Diffusers are normally reserved for pumps that are designed with the impeller(s) between bearings (BB-1 – BB-5) and are very rare for overhung pumps. For more information regarding radial thrust calculation and mitigation techniques, please see Image 1 and my Pumps & Systems column from January 2021.

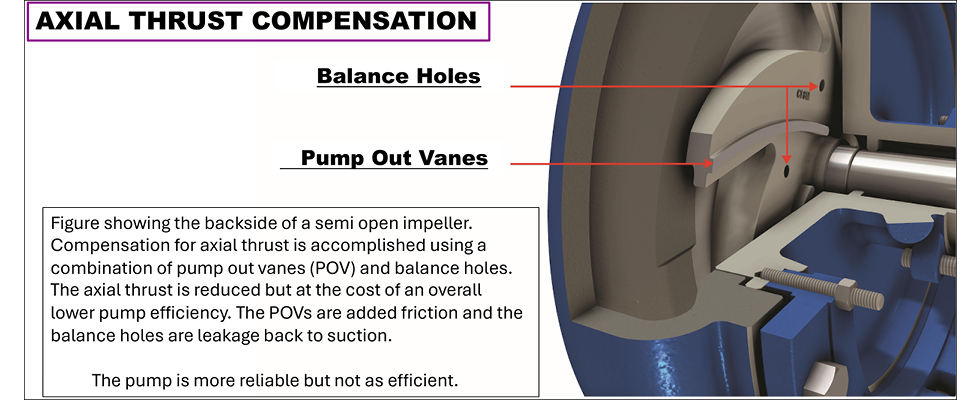

Axial Thrust

Axial thrust is yet another force that must be managed in the overall pump design. The axial forces in the pump exist due to higher pressure acting on one side of a surface when compared to the opposite side. The main axial thrust contributor in the pump is the pressure working on the large surface areas presented by the impeller shroud(s).

For overhung pumps, two common methods for reducing axial force are pump out vanes (POV) on the back side of the impeller and balance holes drilled or machined in strategic quantities, locations and sizes. Both methods work to reduce axial thrust but at the cost of a less efficient pump. For more detailed/technical information on axial thrust, please refer to my series in the August, September and October 2020 issues of Pumps & Systems.

Materials

In my consulting work, I am frequently summoned for forensic analysis of failed pumps. I often witness end users who choose the right pump but the wrong material for the application. You can acquire a pump that is efficient and reliable, and you may think it is a good economic choice until you find out too late it should have been made of Monel or Hastelloy in lieu of cast iron or stainless. Perhaps a future column to expand on good material choices is on the draft board.

Proactive

You can take your own proactive steps to make your pumps more reliable, more efficient and less costly:

- Operate the pump in the preferred operating region.

- Use gauges to determine your position on the curve.

- Use variable speed to stay in the preferred operating region.

- Utilize a balanced impeller (rotor).

- Mitigate or eliminate pipe strain.

- Establish and maintain precision alignments.

- Provide a good foundation.

- Maintain lubrication cleanliness/proper lubrication.

- Set and maintain proper clearances.

- Design for and maintain adequate NPSH margin and submergence.

- Limit the number of startups and shutdowns via system design or variable frequency drives.

- Manage and/or mitigate thermal shock and pressure transients.

- Record and monitor head, flow, vibrations and temperatures (data).

- Manage the recorded data so it becomes useful information and knowledge.

- Educate yourself on proper pump operation and maintenance.

Finally

It is reported that in early March of 44 B.C.E in a heated discussion regarding buying a new pump for the senate fountain, Julias Caesar said to Brutus, “Caveat emptor,”* and Brutus in disagreement replied, “Non caveat emptor. Caveat venditor.”**

But perhaps Meatloaf said it better in 1977: “Two out of three ain’t bad.”

*Translation: Let the buyer beware.

**Translation: Let the seller beware.

References

- The London Metals Exchange, lme.com

- Maintenance and Troubleshooting Single Stage Pumps, Proceedings Pump Symposium #1 1984, W. Ed Nelson, Oak Trust Library, oaktrust.library.tamu.edu

- Process and Equipment Reliability, Paul Barringer, Maintenance & Reliability Technology Summit, May 25, 2004

- Pump User’s Handbook: Life Extension, Heinz Bloch and Allan Budris

- Epic Records, 1977, Bat Out of Hell, Marvin Lee Aday, Jim Steinman, Todd Rundgren