After years of using large internal gear pumps for asphalt flux, a roofing materials manufacturer suffered multiple shaft breaks in a series of pumps. These shaft breaks were uncommon in past usage and were brought to the attention of the pump supplier. The pumps typically operate at 100 gallons per minute (gpm) and less than 100 pounds per square inch (psi) discharge pressure. The system uses a hot-oil heating loop to maintain the asphalt flux at a proprietary high temperature to reduce the viscosity of the product enough to allow smooth flow and reduce pipe wall buildup of solid asphalt flux. The pumps are operated by 30 horsepower (hp), 1,750 rotations per minute (rpm) motors and a gearbox that reduces the pump speed to 100 rpm for product flows of 100 gpm.

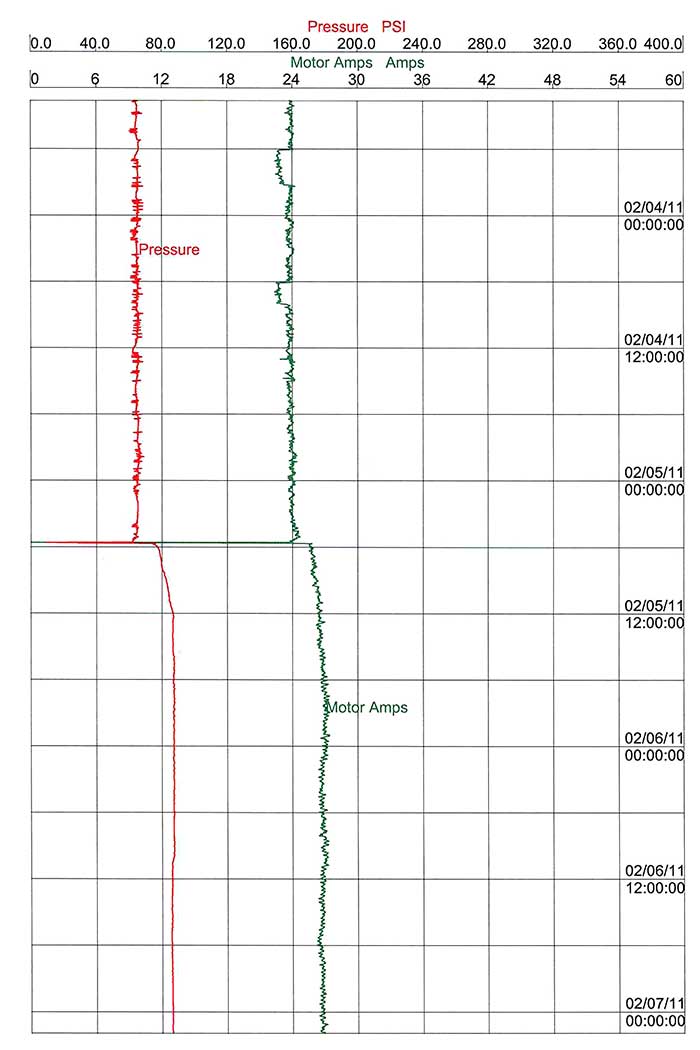

Image 1. Chart sample of captured process data (Courtesy of Carotek, Inc.)

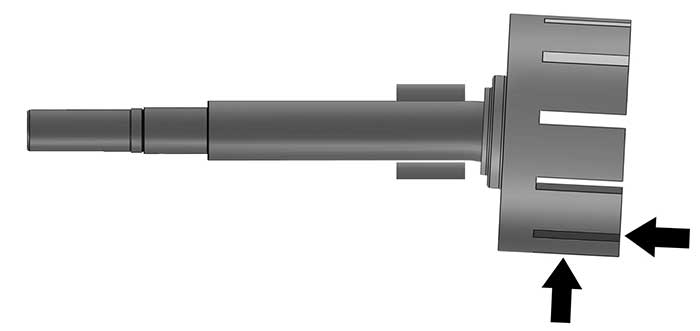

Image 1. Chart sample of captured process data (Courtesy of Carotek, Inc.) Image 2. Shaft turned within the rotor and sheared set screws (Courtesy of Certainteed)

Image 2. Shaft turned within the rotor and sheared set screws (Courtesy of Certainteed)Analysis

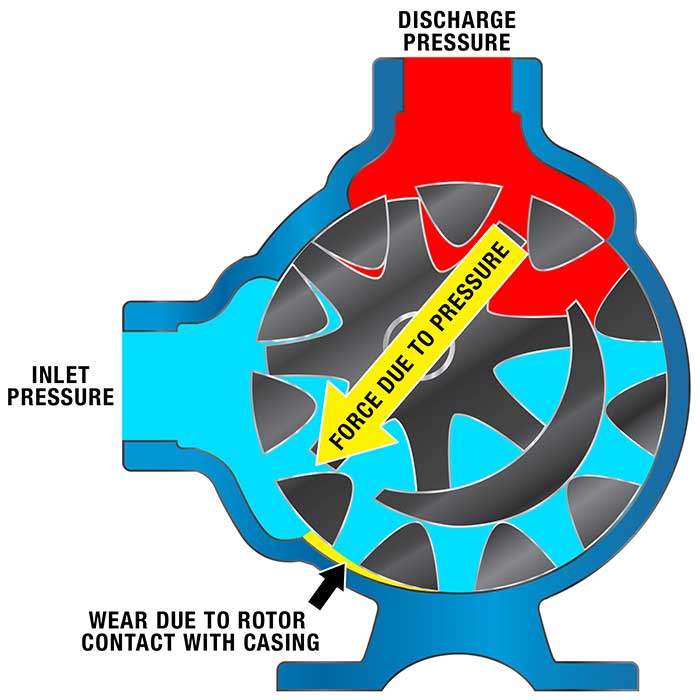

The pump supplier and manufacturer carefully analyzed the pumps with broken or turned shafts. Dimensional checks and metallurgical analysis of the shaft and set screws were conducted. Both were found to be within the manufacturer specifications. Once the pumps were burned out to remove residual hardened asphalt, abnormal wear patterns in the pumps showed excessive discharge pressure had deflected the shaft and forced the rotor into the suction side of the pump casing (see Images 2 and 3). Image 3. Rotor and shaft bend and deflection (Courtesy of Viking Pump)

Image 3. Rotor and shaft bend and deflection (Courtesy of Viking Pump)Resolution

Once these factors were considered, the manufacturer took measures to address the pump shaft deflection, and the facility maintenance team focused on addressing the standard operating procedures. Each group took action to resolve further shaft failures. The pump manufacturer made a design change in the pump to incorporate a larger shaft. The shaft diameter was increased by 40 percent. This thicker shaft helped to reduce the shaft deflection by 66 percent, thus reducing the potential for premature wear and rotor/shaft assembly failure. The larger shaft increased the L/D shaft deflection ratio and increased the maximum allowable discharge pressure to 200 psi. This design change later became the standard for this size pump for all future builds by the manufacturer. There was no change in shaft diameter at the drive end of the pump, so existing power transmission equipment such as sheaves and couplings will still apply to the pumps. The pump supplier placed process monitoring equipment on the asphalt flux pumps to measure process loop temperature, discharge pressure and motor amperage. Recordings were taken electronically every two seconds as well as visually monitored three times per day by the facilities maintenance team for three months. The facilities maintenance team reviewed the standard operating procedures specifically related to shut down and start-up procedures regarding the asphalt flux temperature loop. Changes were initiated to prevent the occurrence of “cold” start-up conditions. Image 4. Wear patterns in internal gear pumps (Courtesy of Viking Pump)

Image 4. Wear patterns in internal gear pumps (Courtesy of Viking Pump)